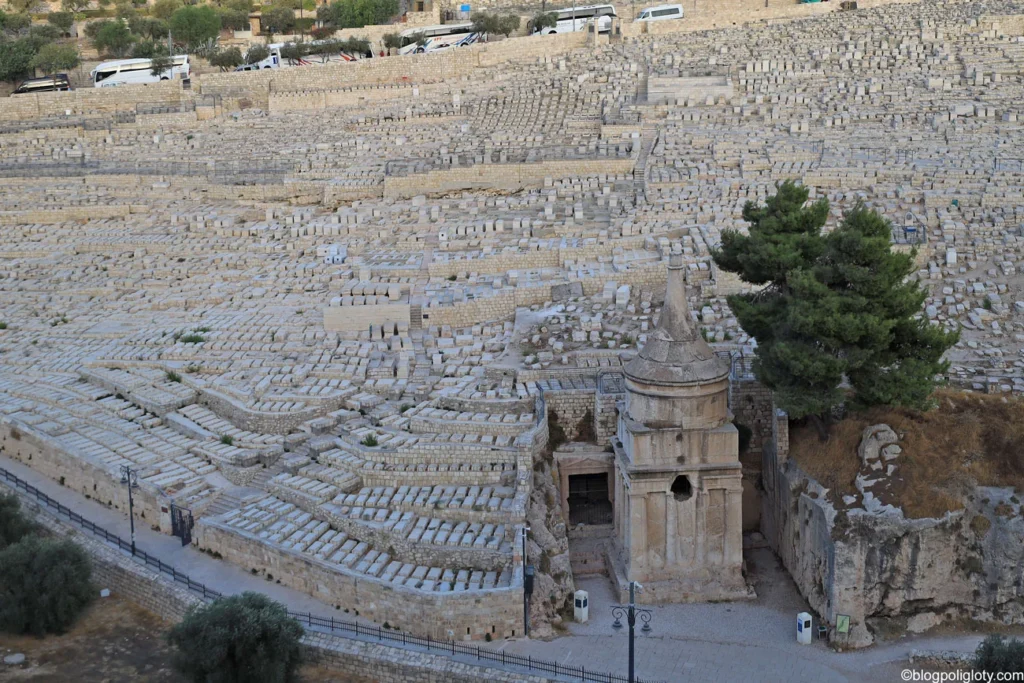

Among the rock-cut monuments of Jerusalem, the structure traditionally identified as the “Tomb of Absalom”, also called “Absalom’s Pillar”, is located in the Kidron Valley in Jerusalem, a few metres from the Tomb of Zechariah and the Tomb of Benei Hezir. It stands out both for its monumental form and for the complexity of its religious history. This square monument, hewn directly from bedrock and crowned with a distinctive conical roof, has attracted pilgrims since at least Late Antiquity. Despite its popularity, its original purpose and later reinterpretations remain subjects of debate, shrouded in mystery.

For centuries, the monument was traditionally associated with Absalom, the third son of King David, who led a mutiny against his father. As a result, it became customary for passersby – Jews, Christians and Muslims alike – to throw stones at it. Inhabitants of Jerusalem would even bring their unruly children to the site to teach them the fate of a rebellious son.

Description

Absalom’s Pillar is about 20 metres tall. The monument stands on a square base and is made of two main parts. The lower part was carved directly out of the rock of the Mount of Olives, while the upper part, which rises above the natural rock, was built from carefully cut stone blocks.

The lower section is a single solid stone block, almost cube-shaped, measuring about 6 metres wide and 6.4 metres high. On three sides, narrow passageways separate it from the surrounding rock of the Mount of Olives. Each side of the monument is decorated with pairs of Ionic half-columns, with smaller columns and pillars at the corners. The four square facades are topped with a Doric frieze and an Egyptian-style cornice.

The upper part of the monument, built from cut stone blocks, is made up of three sections with different shapes. First, there is a square base placed above the Egyptian-style cornice of the lower part. Above this sits a round section decorated with a rope-like band. This supports a cone-shaped roof with curved sides, often described as a “hat”, which is topped by a partly closed lotus flower. The overall shape of the upper part resembles a classical round temple and is similar to Nabatean buildings from Petra dating to the same period.

Inside, the upper section is mostly hollow. A small arched entrance on the south side is located just above the point where the built structure begins. From this entrance, a short staircase leads down into a burial chamber carved into the solid lower part of the monument. The chamber measures about 2.4 metres on each side and contains arched burial spaces on two walls, as well as a small burial niche. When archaeologists first examined the tomb, it was found to be empty.

From Biblical Memory to Monumental Reality

Architectural analysis places the monument’s construction in the 1st century CE. Its façade, decorated with Ionic columns carved in relief, reflects the funerary aesthetics of the late Second Temple period. Over the centuries, however, the monument underwent significant alterations, including inscriptions, symbolic carvings, and episodes of deliberate defacement, each reflecting shifting religious claims over the site.

Although the structure postdates the biblical Absalom (c. 1000 BC) by nearly a millennium, it eventually became associated with the “Absalom’s Monument” mentioned in the Second Book of Samuel (2 Samuel 18:18). According to the biblical narrative, Absalom – rebellious son of King David – erected a monument for himself in his lifetime because he lacked a male heir to preserve his name. Two sources from the 1st century CE attest to the existence of such a memorial in Jerusalem: the Copper Scroll from Qumran (dated shortly before 68 CE) and Flavius Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews (7.243), composed in the early 90s CE. These references likely contributed to the identification of the Kidron Valley monument with Absalom in later tradition.

In 2003, scholars identified a Greek inscription dating to the mid-4th century CE carved into one of the monument’s walls. The text identifies the structure as “the tomb of Zechariah, the martyr, the holy priest, the father of John”, indicating that by this period the monument was believed to mark the burial place of Zechariah, the Temple priest and father of John the Baptist – despite the fact that he lived several centuries before the inscription was made.

That same year, researchers documented a second inscription of comparable date, which designates the monument as “the tomb of Simeon, a man distinguished by his righteousness and devotion, who awaited the consolation of the people”. The descriptive formula applied to Simeon closely mirrors the wording of Luke 2:25 as preserved in the Codex Sinaiticus, a fourth-century manuscript of the Christian Bible, underscoring the deliberate biblical framing of the site during Late Antiquity.

Moreover, a Tau-shaped cross incised into the bedrock opposite the entrance was documented in the late 20th century. The Tau, a form of cross used in the Roman world before the crucifixion of Jesus, became one of the earliest symbols adopted by Christians, predating more familiar signs such as the Chi-Rho. It could convey belief in Christ and the promise of salvation in a discreet and theologically resonant way, at a time when overt representations of the crucifixion were avoided and Christianity was still practiced largely in private or under persecution.

Further inspection of the entrance area reveals faint carvings of an alpha, a partially preserved omega, and a nail or spike – symbols widely associated with early Christian theology and the crucifixion. These elements are visible only under specific lighting conditions, which explains why they escaped notice despite the monument’s prominence. Comparable cases, such as the delayed recognition of the Tel Dan inscription, demonstrate how such factors can obscure significant archaeological evidence.

The discovery of a Tau cross in relief in a Negev tomb dated to the 2nd–3rd centuries CE provides an important parallel. As one of the earliest securely dated Tau crosses found in situ, it supports the possibility that the Kidron Valley monument was Christianized earlier than previously assumed, potentially in the pre-Constantinian period.

A Pre-Constantinian Place of Pilgrimage

Following the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135 CE), Jews were barred from residing in Jerusalem under Roman law. During this period, Christian groups – particularly monks – began assuming responsibility for the care and reinterpretation of sites associated with biblical history. Rather than constructing new religious buildings, they often adapted existing monuments whose original function was unclear or no longer relevant.

The so-called “Tomb of Absalom”, situated between the Mount of Olives and the city, offered an ideal location. Its proximity to eschatologically significant landscapes and its association with biblical memory made it an attractive focus for devotion. The addition of water basins – one plausibly for holy water and another large enough to function as a baptismal font – along with niches for lamps or small statues, suggests that the monument served ritual purposes, even if it was never formally consecrated as a church.

In this light, the site may be best understood as a martyrium: a commemorative space associated with a holy figure, adapted for prayer and pilgrimage. Such a designation would place it among the earliest Christian pilgrimage sites in Jerusalem, predating monumental constructions like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Defacement, Stoning, and the Reassertion of Tradition

The later history of the monument is marked by deliberate erasure and physical damage. The Greek inscriptions and Christian symbols were systematically obliterated, and the structure was subjected to repeated stone-throwing over centuries. In Jewish tradition, stoning carried strong symbolic meaning, often associated with punishment for rebellion or grave transgression, as outlined in passages such as Deuteronomy 21:18–21.

Absalom’s biblical legacy – as a son who rebelled against his father and publicly violated familial and royal norms – may explain why popular tradition sanctioned symbolic acts of punishment against a monument bearing his name. By removing Christian markers and restoring the Absalom association, later communities effectively neutralized the site’s Christian significance and reaffirmed an older narrative grounded in scripture and oral tradition.

Conclusion

The monument in the Kidron Valley illustrates how sacred spaces in Jerusalem were repeatedly reinterpreted by successive religious communities. Initially constructed as a monumental tomb in the early Roman period, it became identified with Absalom through biblical memory, reimagined as the tomb of Zechariah by Christians, and ultimately reclaimed by Jewish tradition through the erasure of Christian elements.

Archaeological features such as the Tau cross, symbolic carvings, water installations, and architectural modifications suggest that the monument functioned for a time as a Christian pilgrimage site – possibly one of the earliest of its kind in Jerusalem. Its later defacement underscores the enduring power of oral tradition, which ultimately outweighed written inscriptions in determining the site’s identity. Whether remembered as Absalom’s monument or as the tomb of Zechariah, the structure remains a powerful testament to the layered and complex religious history of Jerusalem.